After wrapping my Theory into Practice series, I wanted to zoom out a bit and have a slightly more philosophical post this week. Bridge-building between theory and practice will continue to be the bread and butter of Becoming Literary, but there will be weeks when I want to pause and reflect on trends and events happening in education, literary studies, and/or culture.

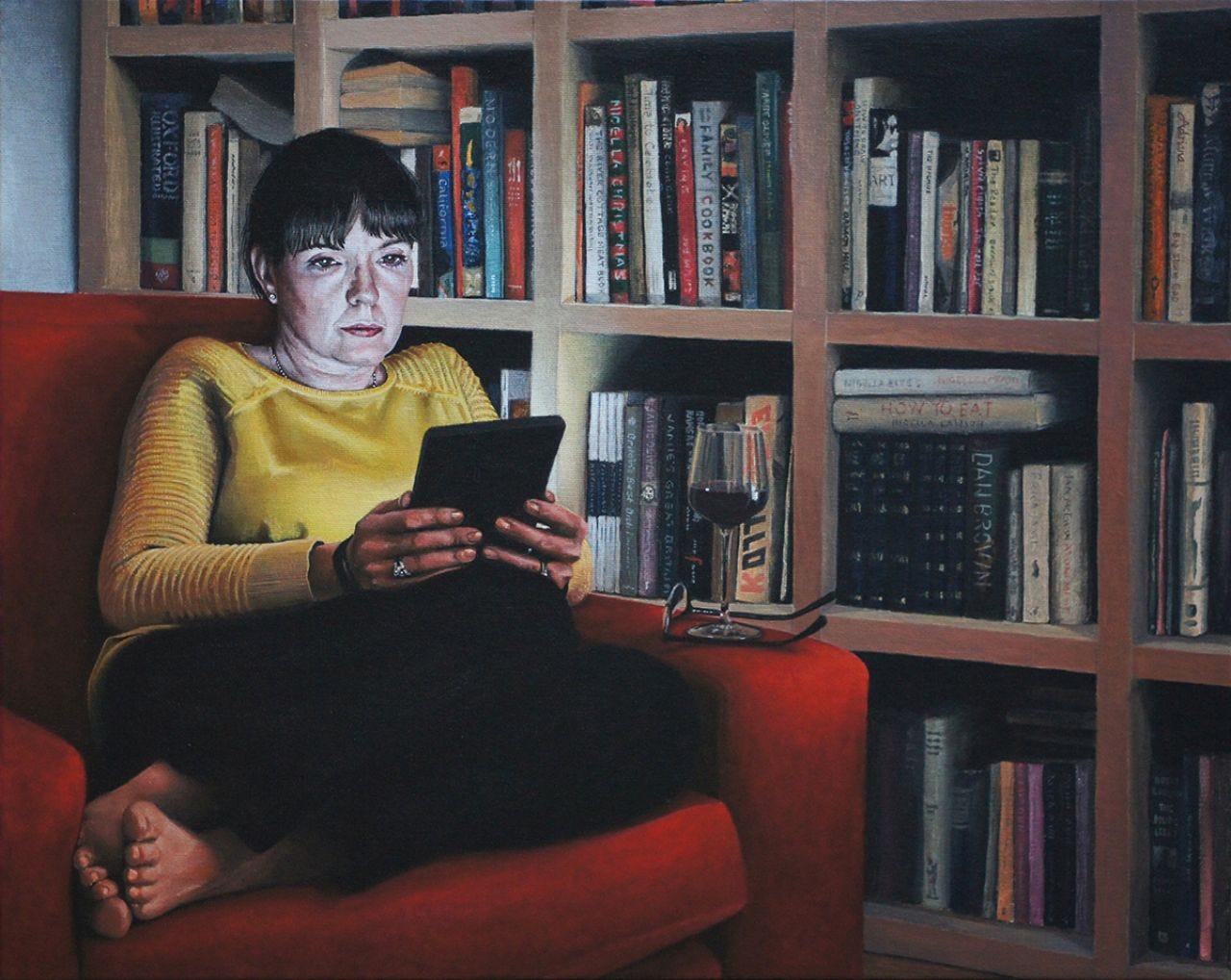

Watching how quickly things are deteriorating in our nation’s capital while the tempo of my suburban New England life ticks along has been disorienting. When I’m not looking at a screen, the rhythms of my daily routine continue slowly and methodically. I wake up. I teach. I come home. I husband/parent. I write. I go to bed. It’s a comforting, albeit exhausting, structure that many young parents can probably relate to.

When I pick up my phone though? Decades happen. Time and space are swallowed up by a deluge of messages, videos, memes, news reports, shitposts, and clips all swirling together on my news feed. Aspirational notes about growing my Substack are placed next to a summary of the latest executive order which is followed by a meme about Game of Thrones. Total context collapse. Utter panic juxtaposed with detached amusement. The last week felt like a year, and every time I looked at my phone, I aged a decade.

Every push notification reads like the prologue to a bad Tom Clancy novel (or the sequel to Idiocracy). It’s starting to feel like whatever I’m reading on my phone is happening in an alternative reality—a reality that is drowning me in stupidity, cynicism, and spectacle. It is equally exhausting and anxiety-inducing.

Guy Debord and The Society of the Spectacle

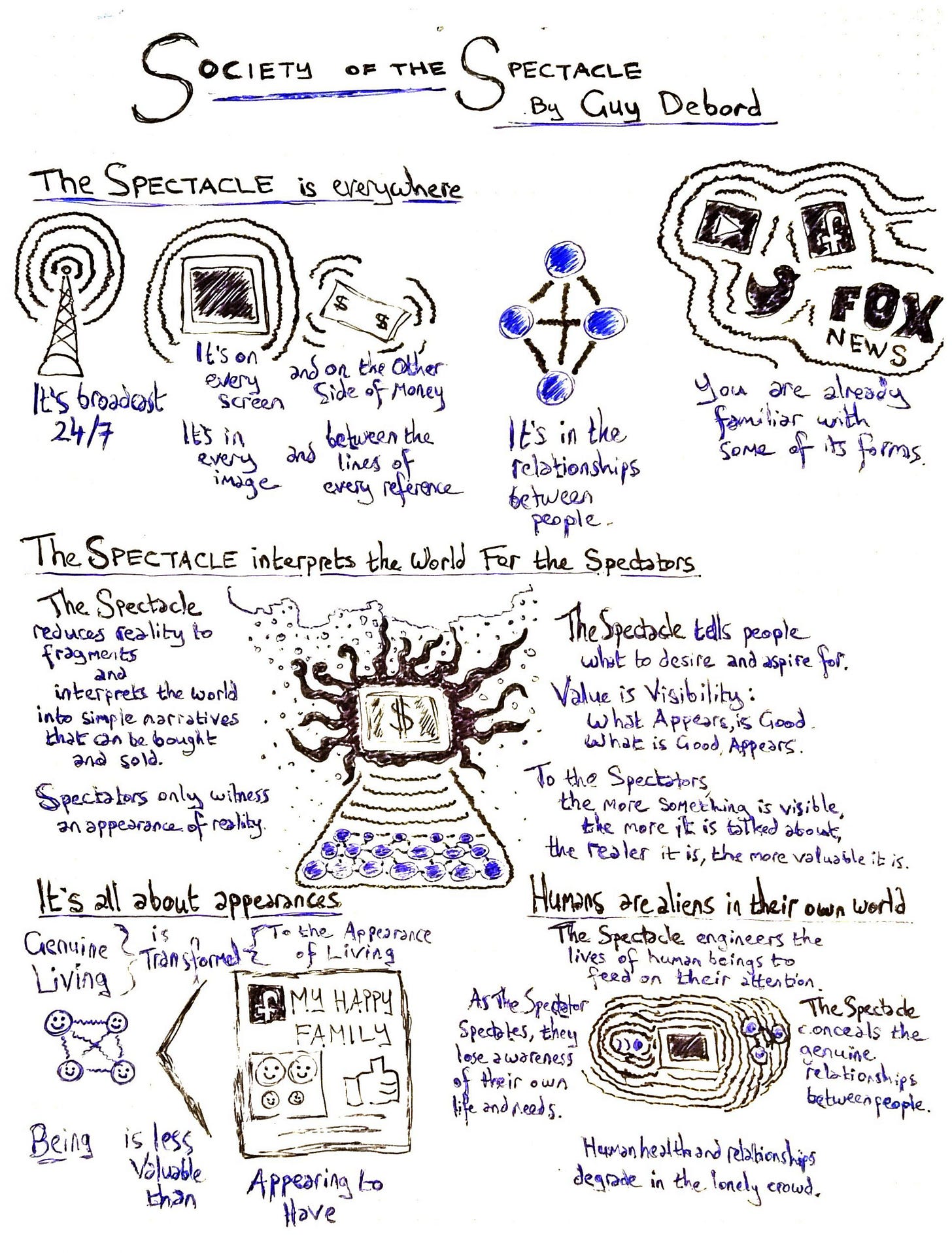

As it happens, a certain French theorist and critic saw this coming long before the recent election, the rise of Silicon Valley’s broligarchy, or even the dawn of the internet. Guy Debord was a key figure in the Situationist International movement and is best known for his seminal work, The Society of the Spectacle—a collection of 221 theses arguing that our modern conditions of production and consumption have created a society where authentic social life has been replaced by its representation; a state where all direct experience has been transformed into a mediated spectacle. Debord defines “The Spectacle… not as a collection of images, but a social relation among people, mediated by images”. In essence, we no longer relate to others through our lived experiences and actions but through our consumption of mass media.

The core issue with this is, according to Debord, that these conditions of production and consumption are fundamentally altering the very social fabric of our society—that those systems use the spectacle to distract us from actually living our lives. By consuming and participating in the spectacle, we become too distracted to actually change these systems and too alienated to realize we even want change. As Debord himself puts it:

The more he contemplates, the less he lives; the more he identifies with the dominant images of need, the less he understands his own life and his own desires.

The TL;DR version: Our economy and media ecosystem make it easier for us to consume reality through our screens than to experience it ourselves. This alienates us from ourselves and other people in ways that stymie actual change and leave us isolated—no matter how many followers or subscribers we might have. If you want a deeper dive, check out this great overview from Tom Nichols.

Rather embarrassingly, one of the best examples that comes to mind is a verse from Drake’s “Emotionless” (I’m team Kendrick, btw).

I know a girl whose one goal was to visit Rome

Then she finally got to Rome

And all she did was post pictures for people at home

'Cause all that mattered was impressin' everybody she's known

I know another girl that's cryin' out for help

But her latest caption is "Leave me alone"

I know a girl happily married 'til she puts down her phone

I know a girl that saves pictures from places she's flown

To post later and make it look like she still on the go

Look at the way we live

Debord would agree with Drake that, for each of these nameless women, the images they consume and produce on social media have superseded the actual experiences, thoughts, and feelings of their everyday lives. The appearance (i.e. representation) matters more than the reality. This critique was just as salient when Debord made it in 1967 as it was when Drake made it in 2018 as it is now, although things have gotten decidedly worse in a variety of ways.

Living in the Age of Spectacle

As if that isn’t dystopian enough, the last decade of politics has been a cascade of mask-off moments for those operating the spectacle machine. The creation and maintenance of spectacle is no longer a skillfully deployed tool for lulling us to sleep; it is now a cudgel used to beat our attention and willpower to a pulp. In addition to manufacturing our desires for consumption, Debord also theorized how it can be deployed for political ends:

Once ideology—the abstract will to universality and the illusion associated with that will—is legitimized by the universal abstraction and the effective dictatorship of illusion that prevail in modern society, it is no longer a voluntaristic struggle of the fragmentary, but its triumph. At that point, ideological pretensions take on a sort of flat, positivistic precision: they no longer represent historical choices, they are assertions of undeniable facts.

When Debord talks about an "abstract will to universality" and "universal abstraction," he's identifying something crucial about our relationship with media and reality. For many people, especially those with relative privilege within society, politics is something typically only experienced directly on election days—instead, most folks experience it through layers of representation: news coverage, social media discourse, viral videos, and algorithmic feeds. These representations don't just describe reality; they become our primary way of understanding it. Press conferences are viral videos. Politicians are influencers. Executive orders are tweets. We are no longer constituents requiring representation; we’re consumers of algorithmically curated political content.

For reasons that should be obvious, the phrase “effective dictatorship of illusion” feels particularly salient right now. Here, Debord isn’t merely suggesting we’re being fooled by false images; he is claiming that one of the primary functions of the spectacle is to become so pervasive and self-reinforcing that it effectively governs how we perceive reality. Whether you embrace or rail against this “dictatorship of illusion,” it can only be experienced as a form of consumption, and thus, its power feels absolute. When all political discourse happens through these mediated forms, it becomes increasingly difficult for us to even imagine alternate ways to engage with political reality. When we consume politics the same way we consume Vanderpump Rules, we are just as incapable of saving Democracy as we are saving Tom and Ariana from Scandoval.

The key insight here is that we've moved beyond simple propaganda or manipulation. The entire architecture of how we communicate and make sense of the world tends to automatically reproduce certain ideological perspectives. The spectacle doesn't need to actively convince people anymore—it shapes the very way they perceive reality.

I know—that’s dark! I am, however, a believer in pragmatic idealism, so here are three ways we might navigate and resist the spectacle in our daily lives.

Create and participate in communities of direct action and mutual aid.

The spectacle thrives when we believe our only avenue for political engagement is through mediated consumption. Whether it's joining a local food distribution network, participating in community gardens, volunteering at a local school event, or organizing neighborhood support systems, direct community involvement lets us experience political reality through unmediated human relationships rather than algorithmic feeds. This isn't just about "doing good"—it's about experiencing political reality in ways that the spectacle can't fully capture or commodify.Develop "spectacle spectacles" to evaluate your daily media consumption.

This means actively examining how different platforms and formats shape our perception of events. For instance, next time you find yourself doom-scrolling through political content, pause and consider: How does this platform's format affect what kinds of ideas can be expressed? How does the need for engagement shape how information is presented? The goal isn't to somehow escape the spectacle (that toothpaste is out of the tube) but to understand how it operates so thoroughly that its effects become visible rather than invisible. This better enables you to follow my third tip.

Practice intentional disconnection and direct experience.

The spectacle maintains power by keeping us constantly tethered to mediated reality. Choose specific times to completely disconnect from screens and news feeds, not as #selfcare but as a deliberate practice of experiencing reality directly. Take walks without your phone, have meals without background content playing, and spend time outside with friends and loved ones. When you do engage with news or political content, do it intentionally—set aside specific times rather than letting notifications fragment your attention throughout the day. This isn't about having a ~digital detox~ it's about creating regular patterns of unmediated experience that help maintain perspective on how the spectacle shapes your perception. Remember: binging anxiety-inducing political content is not praxis.

The goal of these strategies isn't to find some pure, unmediated truth or become one of those annoying people who brag about deleting your social media. Instead, it's about creating small but meaningful spaces of resistance within our daily lives where we can experience reality through direct human connection rather than just mediated consumption. When these things can be done in community with others, that’s even better. Connect with some like minded folk and get started.

PSA: There are a number of policies currently being passed that have a very real impact on people’s material lives, not just their digital ones, so I don’t want to give the perception politics is simply theater or that these tips can replace direct political action and organizing. The whole point of the spectacle is to distract us from those actual issues and prevent us from taking action.

Teaching in the Age of Spectacle

What does this mean for teachers? Quite a lot, actually, though I've simplified it down to two key takeaways.

1. Find ways to resist and critique the spectacle.

This first point tackles one of the most pressing challenges in contemporary education. While teaching students to fact-check sources and identify misinformation is important, it only scratches the surface of what they need to navigate our media-saturated world. We need much more robust conversations about the relationship between media, reality, and ideology. Understanding that dynamic is the difference between media literacy and critical media literacy. Traditional approaches to media literacy often treat false information as isolated incidents that can be corrected through better sourcing or fact-checking. But Debord's framework reminds us that the challenge runs much deeper.

Our students need to understand how the very structure of modern media shapes our perception of reality. It's not just about whether a particular viral video is "real" or "fake"—it's about understanding how the format of viral videos itself transforms how we engage with political discourse. How does reducing complex policy issues to short-form video change how we understand them? How do the demands of virality and engagement affect what kinds of political content get amplified?

These are the deeper questions of media literacy that often go unaddressed in our rush to teach students about reliable sources. I’ll post more on this later, but I’m currently using Kellner and Share’s Critical Media Literacy framework in my classes and students have really been getting a lot out of the deeper engagement with current events. I read their Critical Media Literacy Guide: Engaging Media and Transforming Education book in one of my graduate courses and loved it.

2. Create “anti-spectacle” learning ecologies.

Our classrooms need to be anti-spectacle. We must strive to create humanizing spaces that allow students to meaningfully engage with their peers and feel affirmed in who they are. In a world where students increasingly experience reality through layers of digital mediation, our classrooms need to provide spaces for direct, authentic human interaction.

This doesn't mean rejecting technology altogether—although Debord might side-eye me for saying so (granted he did use the mediums he criticized as tools for critique). Instead, it means being intentional about creating ecologies of learning where students can engage in genuine dialogue rather than fill out boxes on Google Docs, interface with an edtech app, or watch a Khan Academy video. The key is understanding how technology can be a tool to supplement in-person communication and connection, not replace them.

When students collaboratively annotate texts using digital tools, they're not just consuming content—they're actively constructing meaning together. When they create podcasts or video essays about topics they care about, they're not just producing content for algorithmic distribution, they're engaging in authentic communication with real audiences. When they use social platforms to connect with authors, artists, or experts in their field of interest, they're not just networking, they're participating in an interpretive community in meaningful ways.

More broadly, by creating space for students to engage in authentic meaning-making rather than use the latest whiz-bang killer app or test-taking optimization tool, we're creating anti-spectacle moments. When we emphasize the social nature of learning and interpretation, we're pushing back against the isolating tendencies of the neoliberal culture that feeds the spectacle. When we encourage students to bring their full selves to their transactions with texts, we're affirming their humanity in ways that algorithmic content delivery never can.

Wrap Up

The challenge, of course, is maintaining this commitment to anti-spectacle education in a world that increasingly pushes us toward mediated experiences—whether that mediation occurs through egregious uses of technology, the commodification of curriculum, or the maintenance of corporate educational programs. But perhaps that's exactly why it's so important. Our classrooms might be one of the few spaces left where students can experience genuine human connection and authentic intellectual engagement. That's a responsibility we can't take lightly and I don’t intend to! This post ran way longer than intended, but I had a lot to say. I hope you enjoyed a little something different this week!

Appreciate everything about this post—and also reminding myself, more and more, that one of the many privileges of teaching is the "disconnect" the classroom affords in the form of direct experience. Immediacy and proximity are increasingly valuable, and I don't want to take for granted at all what the classroom can be in this moment given that.

Love this post!

A wonderful post Trevor. Thanks for this. Your thoughts on teaching align very closely to my own (creating space for students to have authentic, meaningful experiences in the classroom) but I hadn't considered it from a "Spectacle" perspective before. Subscribed!