Why I Teach Literary Theory to High Schoolers (and you should too)

Helping students read the word and world-system one lens at a time

When I tell people that I teach my 9th graders literary theory, I get a range of reactions: “You’re crazy!” “That’s awesome!” “Isn’t that too advanced?” but my favorite response is: “Why?”

Why indeed! The rest of this post will provide the “long answer” to that question, but the short answer? It is the most powerful thing I’ve done to improve my students’ ability to interpret texts. Curious? Skeptical? Here is what they had to say about learning literary theory in my 9th and 10th grade classes.

Using Theory to Read the Word

As I discussed in my On Interpretation Part 1 and Part 2 posts, supporting students’ ability to analyze texts is probably one of the hardest parts about being an English teacher. We constantly say things like, “Read closer!” “Delve deeper!” “Think more critically!” “Analyze harder!” and (understandably) receive blank stares from our students. One of the most pernicious myths/metaphors that has emerged in our skills-based era is the faulty analogy that our brains are like muscles that need to be exercised to get stronger.

Not only is that analogy wrong, but leads to ineffectual teaching that’s based on a flawed model of how people learn. Worse still, its often deployed in ways that don’t even follow its own logic. For instance, constantly telling an athlete to run harder and faster while they jog fifty laps isn't exactly effective coaching or useful feedback. What makes a difference is giving them the tools to notice technique and think more deeply about how to run effectively. There are a variety of ways to do this—modeling our own technique as expert runners, building their knowledge about different muscle systems, exposing them to strategies and approaches used by other track stars, etc.

Dropping the sports metaphor, teaching students to interpret texts with more depth and nuance isn’t just a matter of practice; it’s a matter of noticing. Literary theory isn’t about burdening students with jargon or mystifying them with arcane academic lore—it’s about teaching them to notice the complex psychological, social, and systemic forces that shape our world, and by extension, the texts within it. It’s about cultivating students’ ability to theorize about how the self, systems, and societies work in stories and equipping them with a language to articulate those dynamics. Or, as Deborah Appleman (2015) puts it in her fantastic how-to guide Critical Encounters in Secondary English:

“literary theory provides readers with the tools to uncover the often‑invisible workings of the text” (p. 3).

All too often, our students’ inability to “think deeply” about texts is misdiagnosed as a lack of “critical thinking” and/or “analytical skills” in ways that treat interpretation like wizardry—some are born muggles, others wizards. Or, more perniciously, in ways that naturalize interpretive acumen (or a lack thereof). As demonstrated by the feedback I shared above, teaching students literary theory allows them to notice psychological, social, and systemic dynamics that they never would have seen otherwise. Sure, part of that is about developing a particular orientation towards and skillset with texts, but it’s also about providing them access to the terminology and conceptual knowledge to name the patterns they notice.

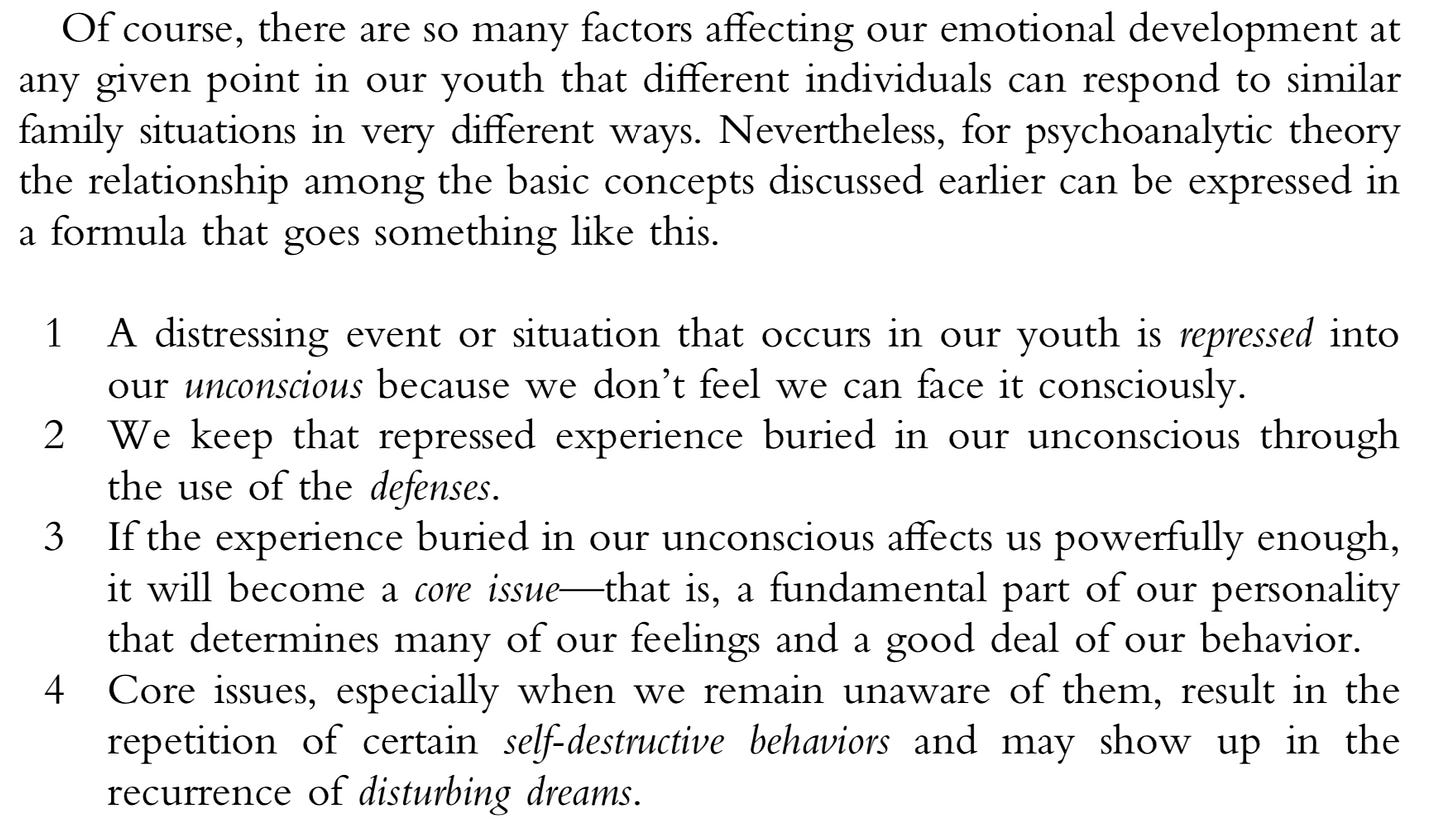

Each theoretical tradition provides students with a constellation of concepts and approaches that can significantly expand their toolkit for literary interpretation. Take, for example, this psychoanalytic framework from Lois Tyson's (2020) Using Critical Theory: How to Read and Write About Literature.

Given that English educators routinely guide students to explore characters' inner lives and motivations (though we may not always label this as psychoanalytic work), imagine how much more nuanced and insightful their analyses could become with access to this kind of specialized knowledge. Consider how much easier it would be for students to apply this framework to a future text compared to asking them to flex their “character analysis” muscles to form an interpretation. Many teachers might not realize it or name it, but we constantly ask students to draw on critical theories every time we ask them to analyze the role of race, gender, class, sexuality, etc., in a text. By not naming it, however, we make it way harder for our students to conceptualize—and thus take ownership of—those interpretive practices.

By introducing literary theory, all I’m doing is surfacing and systematizing concepts and connections that have always been a cornerstone of my curriculum. They were just hidden under the opaque label of “analytical skills”. Now, when learners want to analyze a character’s motivations and desires, they can reach for psychoanalysis. Gender dynamics? Feminist theory. Class dynamics? Marxist theory. Colonialism? Postcolonial Theory. In short, I’m not only giving students the ability to notice those dynamics, I’m giving them a language to name them too. One cannot function without the other.

I cannot tell you the number of students I’ve had who have essentially said they had no idea what to look for or pay attention to when they were asked to analyze a book. They would either guess what the teacher wanted them to say, look it up on Sparknotes, or just give it a vibes-based guess. I think that’s why so many of the comments I shared above see literary theory as revelatory; it helps them see what is possible when they interpret texts, instead of focusing on what is permitted.

There’s a lot more I could say about the benefits of this approach, but I’ll save that for future posts about how I teach literary theory to my students and how they take it up to do interpretive work. Now that I’ve (hopefully) convinced you of the pedagogical reasons I teach literary theory, it’s equally important I dig into some of the deeper social and political reasons as well.

Using Theory to Read the World

To say we live in complex times would be an obscene understatement. The last week alone has subjected us to a dizzying deluge of headlines, conflicts, controversies, and (pseudo?)events that make orienting ourselves feel impossible. While the feeling of disequilibrium might not be distributed evenly based on demographic factors and political persuasions, I think most would agree that the last decade has felt unbalanced if not downright chaotic, regardless of who/what they identify as personally or politically. According to Fredric Jameson, though, this era of fragmentation isn't merely the product of Trump-era chaos or pandemic hangovers—it's the structural logic of how late-stage capitalism has reorganized culture itself. This is something I recently touched on in my Bookmarks post featuring a great explainer from Michael Burns.

This cultural logic, which Jameson refers to as postmodernism, represents the cultural response to our late-stage capital world system and has pervaded every aspect of our daily lives. Where earlier forms of culture maintained some independence from market forces, postmodern culture has been completely absorbed by capitalism. Everything—from art to education to politics—now operates according to market logic. The result is that we've lost our ability to understand our position within the larger system, leaving us politically paralyzed and perpetually disoriented. I don’t want to suggest that these problems can be solved in the classroom, but curricula can serve as a site of sensemaking that gives students the tools needed to better understand our current moment.

Jameson (1991) refers to this sensemaking process as cognitive mapping—a practice that “enables a situational representation on the part of the individual subject to that vaster and properly unrepresentable totality which is the ensemble of society’s structure as a whole” (p. 51). In short, it’s about making visible the totalizing web of historical and material forces that govern our world system and contribute to our collective alienation, disorientation, and subjugation.

Teaching literary theory directly supports this cognitive mapping process by giving students the conceptual frameworks to recognize and analyze the very forces Jameson describes. When students learn feminist theory, they're not just learning to identify gender dynamics in The Great Gatsby—they're developing the ability to see how patriarchal structures operate throughout society. When they apply Marxist theory to examine class conflict in Grapes of Wrath, they're simultaneously learning to recognize how economic systems shape social relationships in their own lives. Of course, this is easier said than done—especially considering we’re attempting it inside educational institutions whose primary purpose is to perpetuate the very systems we’re attempting to critique.

When teaching literary theory with this in mind though, each theoretical lens acts as a different kind of map for understanding power structures. Postcolonial theory helps students see how colonial logic still operates in contemporary global relationships. Critical race theory reveals how racial hierarchies function across institutions. Psychoanalytic theory illuminates how unconscious desires and traumas shape our behavior and are entangled with dominant social and economic systems. Something I love about Jameson is that he doesn’t regard these different theories as competing or contradictory. Instead, he seeks to integrate them into a totalizing “map” that is rooted in historical and material conditions.

What makes this approach potentially powerful is that it moves beyond the traditional English classroom focus on individual texts to reveal the systemic patterns that connect literature to the broader world. Students begin to see that the same forces creating conflict in a novel are the forces shaping their social media feeds, their school policies, and their political landscape. Literary theory, in other words, becomes a toolset for reading not just texts, but the world itself—exactly the kind of cognitive mapping Jameson argues we desperately need to navigate our current moment of cultural and political disorientation.

At the risk of launching a hot take, I have encountered some social justice-oriented programs and pedagogies (whose goals I share!) that emphasize performative displays of guilt, recitation of social justice flavored shibboleths, and/or calling out problematic individuals/texts, over understanding the actual systems that create oppression. That is the difference between Social Justice Teaching™ and teaching for social justice. The former focuses on knowing terminology and performing righteousness; the latter focuses on understanding the systems you hope to dismantle.

When I taught at schools that largely served marginalized students, I didn’t just want them to critique problematic novels; I wanted them to understand how systems of power functioned so they could be dismantled. When I taught at schools that largely served economically privileged students, I wasn’t focused on making them feel shame or publicly acknowledge their privilege; I wanted them to understand how they benefit from unjust systems so they can work towards making them more equitable and democratic. Sometimes I made mistakes. Sometimes I failed. But I tried my best to teach for social justice, not about it.

Of course, even if students do manage to understand these systems, this approach offers no guarantees they will act on their understanding. That is why education is a necessary but insufficient vehicle for social change. What it does offer, however, is an opportunity to make sense of the world in community with others—and that is something worth fighting for. Furthermore, based on what my students have shared with me in person and on end-of-year surveys, it’s something they’re starved for.

Wrap up

A final note—teaching literary theory does not mean there isn’t time or space to devote to aesthetics. As someone who takes their cues from the likes of Jameson, Dewey, and Maxine Greene (despite their differences), I don’t believe you can separate the discussion of social forms and aesthetic forms. Students’ ability to tend to and notice form is intimately bound up in their ability to construct interpretations of both the word and the world. For example, consider how Larsen’s use of an unreliable narrator in Passing creates opportunities for psychoanalytic interpretation. Or how Achebe’s inclusion of Igbo phrases in No Longer At Ease invites readers to reflect on the postcolonial concept of hybridity. In fact, Jameson's entire approach to cultural criticism is built on the idea that aesthetic forms emerge from the historical and material contradictions of their time—and thus yield insight into the nature of those tensions.

So, the reason I teach literary theory is that I want students to make meaning from and make sense of themselves, our society, and our world. Form and content, aesthetics and politics, word and world—they're all part of the same totalizing system that theory helps make visible. In a moment when disorientation feels like the default, giving youth these tools isn't just pedagogically sound, it can be politically empowering. So when people ask me “Why teach theory?” That is why.

References

Appleman, D. (2015). Critical encounters in secondary English: Teaching literary theory to adolescents (3rd ed.). Teachers College Press.

Bracher, M. (2022). Literature, Social Wisdom, and Global Justice: Developing Systems Thinking through Literary Study (1st ed.). Routledge.

Eaglestone, R. (2017). Doing English: A guide for literature students (4th ed.). Routledge.

Jameson, F. (1991). Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv12100qm

Tyson, L. (2020). Using critical theory: How to read and write about literature (3rd ed.). Routledge.

This is all excellent! I love learning about why you teach literary theory. I’ve used lots of different frameworks for analyzing historical documents, but I’ve never attempted literary theory. I’m going to give it a shot next year! I think I’ll start with your NPT framework you discuss in your earlier post.

I completely agree with this! Theory gives students so many possible questions to ask about any text they encounter, whether they’re in the classroom or out of it. I love that you’re doing this and sharing about it here!