Books Cannot Save English (Part 2)

More reasons why literature is necessary but insufficient for transformative teaching

This article is a continuation from my post last week. I’m picking up right where I left off, so feel free to return to Part 1 if you haven’t read it yet.

Students deserve access to the richness and complexity literature offers

…and they’ll likely require meaningful apprenticeship to connect it to their post-digital lives.

Literature deserves a foundational place in the English curriculum. That said, I don’t think it’s immediately obvious to students why they should care about Shakespeare’s sonorous soliloquies, Edgar Allen Poe’s creepy short stories, Frost’s poems of bucolic serenity, or the Lost Generation’s ennui filled modernist novels. Especially if they’re experiencing them as a crucible of assigned readings, quote identifications, and pop-quizzes. Assuming you’re an English nerd, the term “literature” probably has quite a different connotation for you than it does for your students. When you’ve spent your entire life (as both a teacher and student) reading certain types of books written by certain types of people in certain kinds of ways, it’s easy to forget how our relationship with literature is far more mediated than we realize. As usual, Terry Eagleton has it right:

“Literature does not exist in the sense that insects do, and that the value-judgements by which it is constituted are historically variable, but that these value-judgements themselves have a close relation to social ideologies”

Don’t take that as a “everything is relative and quality is arbitrary” style argument though. My guy Terry would slug you for confusing him with wishy-washy post-modernists! Like any good Marxist critic, his point is that concepts like “literature” are historically contingent and ideologically constrained by the system of production under which they’re written and read. In less fancy terms, what we regard as "worthwhile literature" isn't some timeless, universal category that exists outside of history. The books we value, how we read them, and what we think they're for all reflect the material realities and power structures of the society that produces them. This shapes everything from which texts get published to how they're taught in schools to what kinds of writing get labeled as "important" or "great" in the first place.

Point being, just because every student is capable of understanding the devastating beauty of Dostoyevsky or the piercing insight of James Baldwin (and trust me—they are!), doesn’t mean their appreciation happens naturally or organically. Of course, there might be the occasional student who experiences the sublime while reading Wordsworth or Angelou for homework, but we shouldn’t expect it. Nor should we blame students who “fail” to have the aesthetic experiences with literature we think they should—as though books are those pain box things from Dune meant to test students’ concentration, sophistication, and taste.

“How could you hate Wuthering Heights!” we cry at our apathetic classes. “It’s a beautifully written work! It’s in the canon!” as if notions of literary merit hold any meaning for them. “Philistines! Cell phones and social media have ruined the youth. Aren’t they awed by the intricacy of Faulkner’s prose?” we seethe as their eyes glaze over. As if appreciating style is as intuitive as appreciating a sunrise or mountain range. Instead of searching for new entry points for our students, too many educators judge students for refusing to go down the same well-worn path that led them to become English teachers.

So instead of questing alongside our students to chart new pathways, we order forced marches down the same old paths or abandon the journey all together; we turn to fads to engage them, punishments to discipline them, or rewards to bribe them. We forget that our students are experiencing our English class in a post-COVID, post-social media, post smart phone world. The reality is, that means we might have to work harder than ever to help students understand the bounties literature has to offer. In a culture consumed by immediacy, books themselves aren’t the resistance, but they are a site where we can cultivate the skills needed to resist.

It won’t be easy and it won’t happen overnight, but we have got to come to grips with the fact that, if we really want our students to arrive at a point where they see literature in the transcendent ways that we do, it will require us to forge new paths and draw new maps (or excavate old ones?); maps that account for the fact we are living through a moment where the historical tides and social ideologies that structure our lives are completely in flux if not total transition. Speaking of which…

Technology is changing the ways students experience texts

…and that’s why we must leverage its affordances and be aware of its constraints.

Zero-sum thinking drives me crazy. Novels are good. We should teach novels. Do you know what else is good though? Movies. TV shows. Podcasts. Video Essays. Comics. Is it crazy that I think it’s eminently possible to teach literature and incorporate these other aesthetic forms into the curriculum as well? I often encounter variations of these two flattened perspectives.

Books are outmoded. Kids don’t read anymore so we shouldn’t bother. Instead we have to engage them with educational technology and media

Any time spent engaging with a mode other than long form print is, at best, well-intentioned pandering, and at worst, educational malpractice

I’ve never understood why this question creates such rigid binaries, but I think part of it is a lack of imagination and an abundance of assumptions. When some teachers think of full class novels, they think of a class of bored kids getting dragged through a book kicking, screaming, and Sparknoting. They envision homogeneity and teacher-centered pedagogies. When some teachers think of media in classrooms they think of people showing the movie version of books as a low-effort substitute. They envision learners fiddling with apps to make posters filled with superficial fluff. While there are plenty of teachers who are fellow both/and folks, my timeline is also filled with straw men that read a lot like the false dichotomies above.

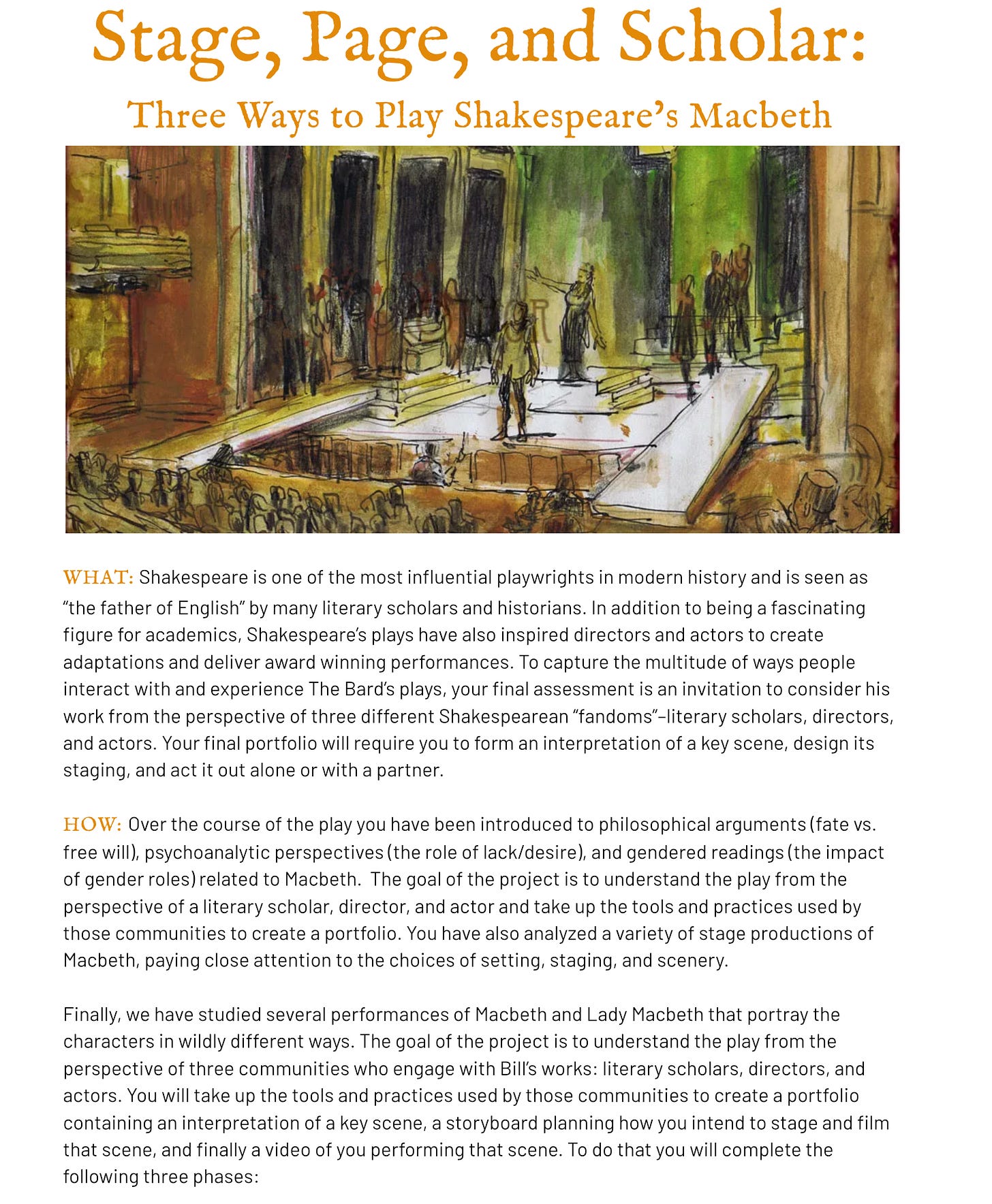

What if, instead, they were able to envision a class where students are positioned as literary scholars interpreting, debating, and evaluating a shared literary work? A space where students leverage literary theory and philosophy to formulate their own highly personalized and unique take on a canonical text? Or what if they were able to envision a unit where students studied various film adaptations of a Shakespearean play to understand how mise-en-scene and cinematography can be powerful tools that shape how an audience experience a narrative? A project where students had to select a scene, develop their own interpretation of its characters, and film it in a way that reflected their analysis?

I know work like this is possible because I literally just taught a unit to my 9th graders that did both of those things1. I had students conducting sophisticated interpretations and writing essays with titles like “Lady Macbeth: A Middle Finger to Misogyny in Macbeth” as well as elaborately shot soliloquies with multiple camera angles, elaborate costuming, pitch-perfect music, and Snapchat filters galore. Here’s an overview.

In addition to alternate forms of media being used to help students experience literary works in new ways, alternate texts can also be put into dialogue with literature. Some of my best units have come from attempts to pair complex literary works with contemporary media exploring the same or similar themes. I want students to consider what Tupac and Whitman might have to say to one another about self-expression. I want them to consider intersections between Beyoncé’s Lemonade album and Toni Morrison’s Sula. I want them to share with me how their reading of Simone de Beauvoir can unearth insights into the school’s production of Legally Blonde or the latest TikTok trend. When students come to understand they can study literature and popular culture through the lenses of form, criticality, and humanity they approach it differently. They begin to see that texts that might seem dusty have something worth hearing, worth exploring—and hopefully they teach us a thing or two about their own literacies and interests along the way.

Two terms I often use when considering which aesthetic forms to use in a given unit are affordances and constraints2. Both concepts actually originated in ecological psychology through the work of James J. Gibson in the 1970s. Gibson proposed that animals (including humans) perceive their environments in terms of what they offer or "afford" the organism. These ideas were later adapted by scholars in multimodal literacy like Gunther Kress, Carey Jewitt, and the New London Group to help explain how different modes of communication enable and limit meaning-making in distinct ways. They’ve also been explored from a literary perspective in Caroline Levine’s fantastic work Forms.

An affordance isn't just a feature of a medium—it's what the medium makes possible in terms of meaning-making. For instance, novels allow authors to unravel deep and complex narratives over the course of several hundred pages. Constraints, on the other hand, are the limitations inherent in that medium. Both are essential parts of the meaning-making ecology, not just technical aspects to be noted and set aside.

Consider the iconic advertisement from the final season of Breaking Bad where Bryan Cranston's character, Walter White, reads Percy Bysshe Shelley's "Ozymandias." The poem itself on the page affords readers a certain experience—the ability to pause, reread, and contemplate the imagery of the shattered monument in the desert. But Cranston's reading, coupled with the visual imagery of the New Mexico desert that evokes the poem's setting, affords viewers a different experience entirely. His measured delivery and the stark visuals create a powerful foreshadowing of Walter White's crumbling empire and allow the viewer to experience the flow, tone, and meter of the poem.

The audiovisual medium affords this layered experience that connects the literary work directly to the show's themes in ways the printed poem alone could not. Furthermore, it provides a new entry point to engage with the ideas Shelley’s poem is meant to explore. Far from distracting students from the poem itself, it serves as a bridge that allows them to see the connection between what’d otherwise be seen as archaic poem and contemporary questions of power, legacy, and mortality.

Or think about graphic novels, where the interplay between text and image creates meanings that neither mode could accomplish alone. Scott McCloud's concept of "closure"—the mental work readers do to connect separate panels into a continuous narrative—is an affordance unique to comics. It's not just that comics "have pictures"—it's that the spatial arrangement of sequential art on a page affords particular types of meaning-making that pure text or moving images cannot. I don’t assign graphic novels because they are easier than print novels. I assign them because they provide an opportunity for students to understand the unique form and function of visual communication.

So instead of focusing on which novel I think my students have to read or which EdTech tool is currently the shiniest, I’m asking a different set of questions. Which texts (be they canonical or digital) will best allow students to explore a theme, concept, or event that our classroom community cares about? Or is important for them to understand? Or will help them advocate for social wisdom and global justice? What are the affordances of whatever aesthetic forms I’ve selected? How can I help students interpret its codes and conventions? How can I help students harness those codes and conventions for themselves so they can produce authentic compositions? These are the questions I ask to build out dynamic text sets that, rather than distract students from literature, gets them excited to dive into the text in search of answers that transcend time, place, and space. This is what I mean when I say we need to forge new paths and construct new maps. It all starts with what texts, practices, and purposes we are using to co-create learning with our students.

Wrap Up

I think I’ve made it abundantly clear that I both love literature and am not convinced it is a panacea for transformative teaching. For better or for worse, we are teaching in a time of transition. That doesn’t mean that literature from the past is no longer relevant, quite the contrary in fact! It does, however, mean that we can’t expect novels to reach across time and space to magically transform students on their own accord. They are tools, powerful tools even, that can help our students better understand themselves and our world, but they rarely can accomplish that in a vacuum. In my opinion, our task as English educators is to do whatever we can to maximize the number of students who understand what literature has to offer, more than it is to make them love reading. No shade to books, but that’s just too important and too human of a task to entrust to pulped wood and cardboard stock.

Until next time!

It’s important to note that I’m privileged enough to be working at a school that encourages this type of teaching and learning. Though I believe this type of teaching is possible in most schools, I’d never deny I have less hurdles than most.

I might use them too often. My colleagues have joked if they took a shot every time I used them in our meetings it’d be the deadliest drinking game ever.

Always enjoy reading your posts, particularly for the push they provide to keep challenging ourselves as English teachers to go further, and imagine further!

I do think that the stubbornness we see from those who do not want to change (*raises hand* at times, too!) comes from a lack of confidence in how they see themselves in that "changed capacity" of the English classroom.

To offer a personal example, while I brought poetry into my classroom from Year 1 onward as a teacher, I never felt comfortable with it and therefore limited our exploration of it pretty considerably—until 2020 hit, schools closed, and for those initial months I had time to take a MOOC (those things can work!) on Modern and Post-Modern American Poetry, literally watching the professor facilitate small-group conversations on every single poem with this class on video. 20+ hours of my own learning later, I felt reborn as a teacher of poetry—and there has been TONS of poetry in our classroom ever since.

My point in sharing that example: we need to create more "onboarding" experiences for teachers to situate themselves as learners, I think, and to experience what it is like to immerse different media/technologies into the classroom to make the most of their affordances (love that term) without also falling prey to their constraints.