Bridging The Theory & Practice Divide in English Classrooms

How I leverage research from literary studies, literacy studies, and cognitive science to design engaging ecologies of learning

One of my goals of this Substack is to translate theory into practice. My opening posts have been my attempt to frame my views on teaching English—what I think it is, why I do it, where my beliefs come from, and the scholarship that informs my perspective. While I think these are vital parts of any teaching practice, I’m also incredibly excited to share how this shapes my teaching. Like every educator, I’m still a work in progress and am always in search of ways I can improve (this is Becoming Literary after all) so I hope these suggestions are taken as invitations and not prescriptions of what is “best”.

Theory 🤝 Practice

If you’ve been following my Substack series, you’ll know one of my primary goals is to empower students to better navigate various discourse communities in both academic and nonacademic spaces. Due to my expansive views of what it means to “Do English” that means I need to cultivate the knowledge and skills required for students to participate in a variety of these communities–ranging from literary studies to the Swifty Fandom to civic and professional spaces and everything in between. While I’ve provided some classroom anecdotes, this post is all about what that looks like in practice.

The relationship between theory and practice isn't just an academic exercise – it's fundamental to effective teaching. As Baker (2010) argues, "teachers who understand a range of theoretical perspectives and their pedagogical implications are more empowered to be reflective than those who do not" (p. 23). This reflection is precisely what enables us to adapt our teaching to suit the diverse discourse communities we want our students to encounter. For that reason, I'm going to situate the strategies I share in Drs. Cope’s and Kalantzis's theory of participation—a framework that regards participation as the dynamic interplay between interpretation, communication and representation that occurs within and across various communities.

This means that all forms of participation are shaped by the social context in which they occur—e.g. soccer players communicate very differently on the pitch than chemists do in a lab, literary scholars interpret literature very differently than policymakers do econometric data, etc. That means both generic 21st century skills and traditional decontextualized learning leave our students devoid of the conditional knowledge needed to navigate and participate in communities beyond our classroom.

With this theoretical foundation establishing the importance of context-sensitive teaching, we can begin to explore what meaningful participation looks like in practice. The key is translating these abstract concepts into concrete pedagogical moves you can make in your classroom.

Towards Meaningful Participation

After considering the key questions of form, humanity, and criticality that structure the field of literary studies and inform my courses (see my previous post for more on that), I use these three questions based on the theory of participation to start my planning:

What knowledge and practices will my students need to interpret the texts we’ll explore in this unit?

What knowledge and practices can my students use to represent and make meaning of their ideas?

What knowledge and practices will my students need to communicate their understanding to an authentic audience?

The next few weeks I’ll be doing a deeper dive into these three questions, but I’ll start with a brief definition before we get into the nitty gritty.

Reading the Word & the World

Among the three core practices of participation, interpretation serves as our foundation. When we talk about interpretation in its broadest sense, we're really discussing how humans make meaning from the world around them - whether that's objects, experiences, or texts. Transcending mere comprehension, interpretation isn't just about understanding what's on the page or screen. Instead, it asks our students to become active knowledge producers, developing their own unique formulations and explanations of texts rather than falling back on pre-packaged answers from their teacher, Sparknotes or, as has become increasingly common, ChatGPT. I think it’s fair to say that most English teachers regard this as one of the most important, but also one of the hardest practices we teach our students. I’ll be doing a deep dive into the approaches I use in my classroom next week, but here’s a preview.

Making Meaning & Making Sense

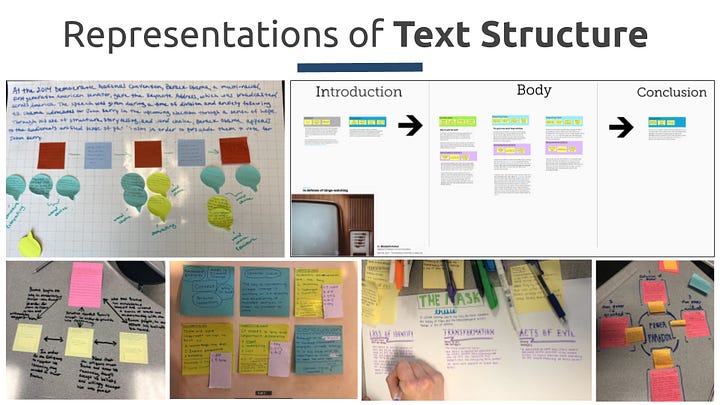

While interpretation focuses on how we construct meaning with objects, texts, or phenomena, representation is what we do to make meaning/sense of a text ourselves. While there are many ways to help this meaning-making process along, visuospatial thinking tools are a key part of my classroom practice. As humanities educators, we're constantly asking students to wrestle with abstract concepts, whether they're exploring the social nuances of Victorian England, deconstructing complex current events, or considering how to best structure a podcast.

While both prior knowledge and a suite of heuristics both play a central role in making sense of complexity, leveraging the affordances of visuospatial reasoning is an oft under utilized and incredibly powerful practice of representation that I rely on in my classroom. I’ll go into more depth on this the week after next, but in the meantime, here’s some examples that might pique your interest.

Students as Knowledge Producers

The final part of the tripartite framework is communication, or the production of texts and meanings that are accessible to others. Once students have formed their interpretation, designed their narrative, or prepared their position it’s vital they’re given the opportunity to share their ideas using the genres and text types that are used in whatever community they are participating in. That might look like submissions to a literary criticism journal, a podcast about Taylor Swift’s era tour, or a TikTok analyzing a trend in popular culture. Here are some examples of what that looks like in my classroom. I’ll be doing a deeper dive in another post soon.

Every unit I design and every lesson I teach is built on these three interconnected practices—interpretation, representation, and communication. They provide my students with the structure needed to address the contextual nuances required to participate in distinct discourses, while affording the flexibility to navigate across them.

Next week I’ll do a deeper dive into the approaches I use to cultivate students’ ability to interpret texts. For me, it’s the most challenging and most interesting of the three, so I hope you’ll give it a read.

References

Baker, E. A. (Ed.). (2010). The new literacies: Multiple perspectives on research and practice. Guilford Press.

Cope, B., & Kalantzis, M. (2020). Making sense: Reference, agency, and structure in a grammar of multimodal meaning. Cambridge University Press.

Trevor, loved this post.

Hey Trevor, I’m still a little unsure about the distinction between interpretation and representation. So interpretation is the practice of making meaning in a text, and representation is how we formalise it? I like the rigour here, and just want to get my head around it, if possible. Thanks for the article! 😊