Communication As Participation

Inviting students to compose and create literary knowledge in community

This is a continuation of my series examining what I regard as the three key practices of English teaching: interpretation, representation, and communication. Each post in the series is meant to stand on its own, but if you want to get the big picture check out my “Overcoming the Theory/Practice Divide In English” post.

Sometimes I forget I’m weird. It usually happens a few seconds into explaining to a colleague, acquaintance, or teaching peer what my research interests are or what my students are working on. “Your class is making a podcast? How interesting” they’ll say with confusion or disdain (or both). “How do you grade a video essay?” they’ll ask, furrowing their brow.

It’s easy to forget that when most people hear “podcast” they think of Joe Rogan ranting about ivermectin or reality show starlets cashing in on their fan’s parasociality. They don’t think of tenured philosophy professors yapping about Lacan and Marx or literary scholars discussing the current state of literary criticism.

Similarly, when most people hear “TikTok,” (RIP?) they think of dancing tweens and viral music trends. When they hear YouTube they think of silly sketches and Minecraft videos. They don’t think of psychoanalytic interpretations of Great Gatsby or in depth breakdowns of Barthes’s Mythologies.

Of course, I’m far from the first person to use digital and multimodal tools in English classrooms. According to Dr. J Palmeri, there is a rich, century long history of educators using multimedia in the English classroom (I’ll be re-releasing my Conceptually Speaking episode with them later this week). That said, based on the research I conducted for my dissertation, there’s not a ton of overlap between educators/researchers experimenting with digital tools and educators/researchers invested in the type of sophisticated interpretive work I’ve been covering so far in my series.

Now, I find that rather odd considering there is an explosion of communities and creators on YouTube, TikTok, Spotify, Substack, etc., exploring dense academic topics and garnering millions of viewers. For great examples of this check out some of the creators listed on our #HackYourStack digital mentor text database.

also does a fantastic deep dive on how this is impacting the field of literary studies in an episode of his American Vandal podcast (which I’ve been bingeing for weeks).In essence, the lines between traditional academic forms of composition and digital, multimodal composition are becoming increasingly blurred. As an educator with an affinity for both, this excites me greatly. Over the last few years, I’ve spent a lot of time thinking of ways I can leverage that fact to design projects that prepare students to meaningfully participate in literary studies while also stretching its boundaries in secondary spaces.

The rest of this blog will provide an overview of assignments and projects I’ve designed that invite students to use the tools and practices of different interpretive communities and communicate with authentic audiences.

Blogging as tool for participatory knowledge production

Blogging in the classroom isn't just another tech tool—it's a way to make interacting with literature more participatory and social. Blogging creates a unique public domain where students can share thoughts and engage with readers through comments and replies, making it distinctly different from traditional writing assignments that frame interpretive work as a decontextualized and individualized process.

When we give students a real platform to share their ideas—not just notebooks passed between desks or shared Google Docs—their relationship with writing shifts. The use of these platforms intentionally centers the social and collaborative aspects of academic discourse and knowledge production. That’s not to say notebooks and Google Docs are “worse” than blogging platforms—I use both frequently—just that they are different. We used Edublogs as the host for our class blog. I appreciate that it gives students experience with the same block editing tools they'll encounter on platforms like Substack (hey there!) and WordPress. However, the technical aspects are secondary to the deeper shifts in learning.

Moving beyond traditional assignments means reimagining how students interact with literature. Simply digitizing conventional short-answer questions or short-form writing responses is a missed opportunity. Through blogging, students become producers of knowledge rather than just consumers of it. I don’t have to ask them to pretend to be literary scholars writing for an authentic audience—the social nature of their writing is baked into the very tools they’re using to compose. This is reinforced by the fact students have to post, read, and comment on their peers’ blogs.

In my classroom, students use blogs to pursue lines of inquiry, explore their thoughts on class novels, and begin sketching out ideas that may inform their final paper. For instance, during our unit on Nella Larsen's Passing, students studied her use of form, interrogated representations of motherhood, considered the relationship between race and class, and leveraged psychoanalytic theory to understand characters’ desires more deeply.

Success with this approach requires careful scaffolding. Like any complex skill, students need to see expert modeling. I demonstrated how literary scholars approach novel analysis, walking through my thought process as I crafted blog posts. Together, we examined example posts, analyzing everything from content choices to structure to writing craft. Here’s a snippet of one I wrote for my students. You can read the full one here.

This modeling matters because we're initiating students into a distinct way of thinking about and engaging with literature. As I’ve been discussing in this series, literary interpretation differs fundamentally from historical or scientific analysis and blogging allows learners to constantly revisit, practice, and experiment with those practices. Better still, it takes the rather abstract notion of “participating in an interpretive community” and makes it tangible for students.

Podcasting as a tool for interpretive discourse

Another way I’ve explored having students share their interpretive work is by having them record podcasts. As Sharon (2022) points out in her recent scholarship, podcasting occupies a unique space in media studies—not quite radio, not fully platformized like YouTube, but offering distinctive possibilities for academic discourse and creative expression. I’ve deployed podcasting in a number of ways, but to provide context I’ll zoom in on one particular project I recently developed for my Global Literature class. I have seen lots of examples of podcasts being used as a way to review books, summarize readings, and provide some analysis, but I really wanted to push my students to use it as a tool for rich literary criticism in this project and they really blew me away.

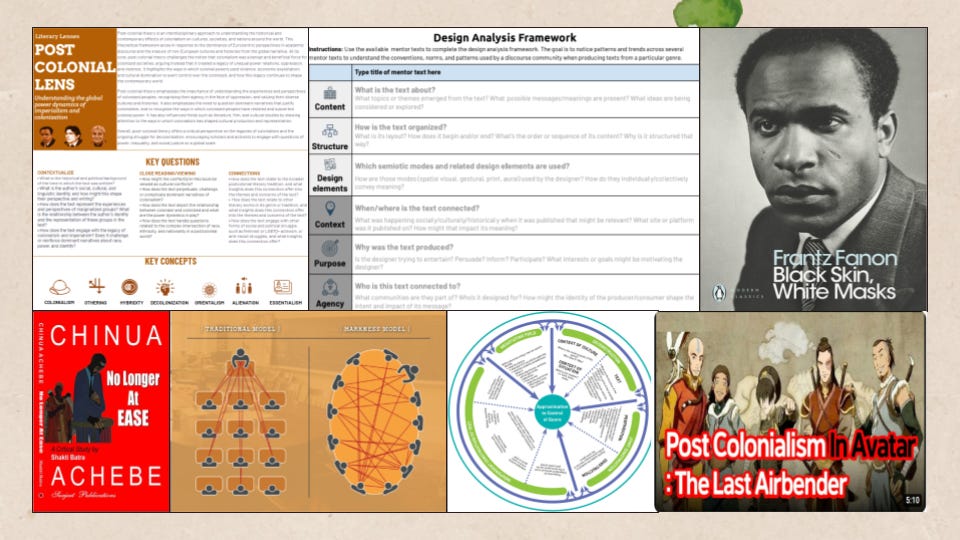

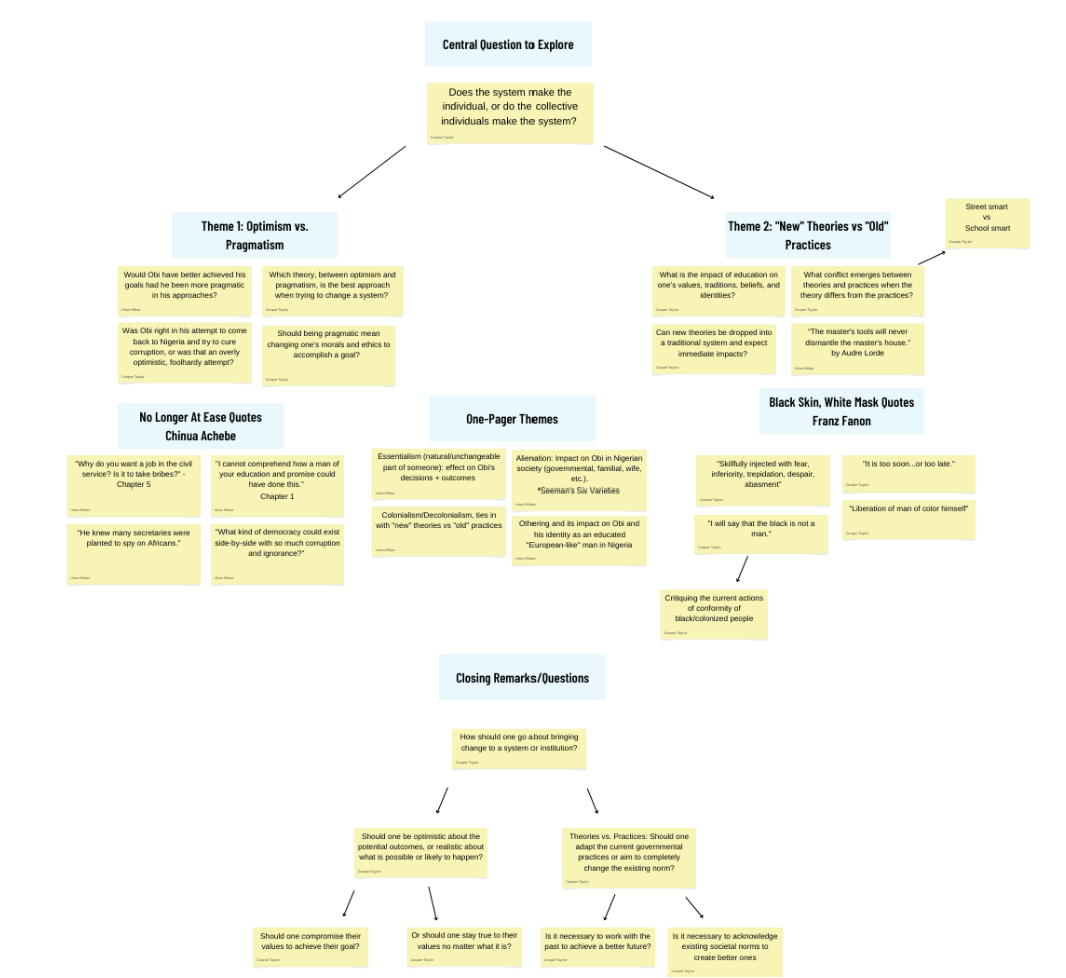

One of the units needing tweaking in our 9th grade interdisciplinary humanities program was our approach to teaching Chinua Achebe’s No Longer At Ease alongside our History department’s deep dive into past and present forms of colonialism. In an effort to infuse the unit with the practices I’ve been covering in this series, I scrapped the existing prompted analytical essay and challenged students to position themselves as postcolonial literary critics speaking to fellow scholars and readers. Working in small groups with the text, secondary sources, and my Postcolonial theory one-pagers, they created 20-minute podcast episodes that pushed well beyond plot summary into forms that more closely resembled actual literary criticism.

The shift in student engagement was notable. When learners know they're creating content for real listeners—not just their teacher—their approach to literary interpretation deepens. Considering their focus was on the content of the text and less on the formal aspects of writing, I was able to push them to bring in more secondary sources. Students referenced excerpts I’d assigned from Fanon’s Black Skins, White Masks, cited primary historical documents discussing the horrors of colonialism in Nigeria, and clipped interviews from Chinua Achebe himself to support their interpretations.

What makes this assignment particularly powerful is how it combines rigorous literary criticism with creative expression. Students aren't just summarizing plots—they're developing original interpretations of Achebe's themes, supporting their analysis with textual evidence, and presenting their ideas in a compelling audio format. Think of it as a more polished, produced version of our classroom Harkness discussions—which can be amazing but are also ephemeral.

This shift from traditional essays to podcasting aligns with broader changes in how academic knowledge circulates in digital spaces. As podcast studies scholars have shown, the medium offers unique opportunities for deep engagement with content while developing new forms of digital literacy. The collaborative nature of podcasting also creates what educational researchers call peer-supported learning environments, where students naturally scaffold each other's understanding of complex literary concepts. Similar to blogging, it provides an opportunity to participate in the discourse of literary studies in ways that feel tangible and real.

Audiovisual essays as form and process

Similar to blogs and podcasts, I know I’m far from the first person to have students create videos in their English class. That said, I’ve not encountered many researchers or practitioners who tend to the fact there are communities of creators and consumers whose interactions shape the content and form of video essays as a genre. This means that video essays go beyond offering students a way to do the same analytical work using fancy technology, but serve as an invitation to engage with an existing community actively engaged in using those multimodal tools to transform how literary, critical, and interpretive knowledge are produced and disseminated.

Based on my emerging research and experiences, using audiovisual tools to share interpretive work enables students to draw from and expand their semiotic repertoire when communicating their ideas. This not only expands the form of literary interpretations, it can influence the content as well. Better still, it recognizes their diverse literacy practices as legitimate tools for academic discourse

When creating video essays, students aren't just putting random images on screen or recording themselves read an essay—they're orchestrating a complex interplay of visuals, sound, and text to represent their interpretations. This isn't just about making analysis more "engaging" (though that's often a welcome side effect). It's about inviting them to use their knowledge-in-action to participate in both academic literary discourse and contemporary digital spaces.

Let me share how this plays out in practice. Last year, I designed a TheoryTok and Gatsby project that invited my students to pick a literary lens, form an interpretation of The Great Gatsby, and communicate it using short-form video. It's an illustrative example of how I try to invite students to merge their existing digital literacies with the practices of literary studies

What made this project particularly powerful wasn't just the analytical insight (though that was excellent). It was how the student leveraged the affordances of the platform—quick cuts, overlay text, background music—to build their argument. They weren't just doing literary analysis in a TikTok format; they were using TikTok's formal elements and genre conventions to enhance their analysis. A few examples:

Using a get-ready-with-me TikTok to conduct a feminist critique of Daisy’s submissive behavior to Tom

Using images to visualize the relationship between Gatsby’s id, ego, and super-ego

Using text and AI-generated voices to signal the use of textual evidence from secondary sources

Excerpting clips from the film to supplement their close reading of key moments in the text

The key is treating this as serious academic work while honoring students' creative agency, funds of knowledge, and youth culture. To prepare them for this work, we spend time analyzing how other creators in these spaces construct their arguments, discuss the affordances of different creative tools, and have detailed discussions about how design choices can serve their analytical purposes. I also have them complete a Design Analysis Protocol as a way to dig deeper into existing conventions and built out their repertoire of semiotic tools.

Wrap Up

In sharing these three approaches - blogging, podcasting, and video essays - I'm not suggesting we need to completely revolutionize how we teach literary analysis. Rather, I'm inviting us to consider how we might expand what counts as legitimate academic discourse in our classrooms. When we create spaces for students to merge their existing digital literacies with the practices of literary studies, we're not just making analysis more relevant or pandering to young students, we're helping them see themselves as legitimate producers of knowledge.

Whether they're crafting blog posts about motherhood in Passing, producing podcasts analyzing colonialism in Achebe’s novels, or creating TheoryTok content about Gatsby, they're engaging in sophisticated interpretive work that honors both academic rigor and their own creative agency. That’s what becoming literary is all about!

Next week I plan to do a follow up post where we look at how I invite students to compose in other genres, forms, and modes.

References

Sharon, T. (2023). Peeling the pod: Towards a research agenda for podcast studies. Annals of the International Communication Association, 47(3), 324–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2023.2201593