On Teaching Interpretation (Part 1)

Tangible tools for improving students' interpretive practices

This is a continuation of my series examining what I regard as the three key practices of English teaching: interpretation, representation, and communication. Each post in the series is meant to stand on its own, but if you want to get the big picture check out my “Overcoming the Theory/Practice Divide In English” post. As it turns out, I have a lot to say about interpretation, so that section will be broken into two parts. Enjoy part one!

Last week, I participated in a serendipitous BlueSky exchange that seemed like the perfect setup for my planned post. As any English teacher will tell you, discussions about what books we teach in our class generate a lot of feelings—from peers, professional networks, parents, and, increasingly, policymakers. While these discussions are undoubtedly vital, especially in our current moment, I’m inclined to agree with

—discussions of what texts we teach often overshadow dialogue about how we teach them.Speaking as someone who has used The Lorax to teach Marxism, Black Panther comics to frame postcolonial theory, translations of Beowulf to examine our contemporary obsession with Marvel movies, and paired literary criticism with TikToks about the Kardashians, I can assure you required reading lists only offer a glimpse into what happens in a classroom. Hopefully this post can generate some dialogue about how/why we teach texts to compliment conversations about what texts we teach.

Considering the incredibly contextual nature of teaching and the rich multi-faceted nature of English as a discipline, there are an infinite number of ways to approach these “how?” questions. I do think most teachers, however, would agree that teaching our students to form interpretations is the sine qua non of literary studies. It is certainly a central part of my teaching, at least. In fact, I start each year discussing the importance of interpretation with my students by having them engage with a chapter of Robert Eaglestone’s fantastic text Doing English—especially the point demonstrated in this graphic.

This excerpt highlights a crucial but frequently neglected dimension of discussions about teaching literature: not just what we teach, not just how we teach, but how we present and frame the very acts of reading and interpretation. Looking back at my early teaching career, I now realize I used teaching methods that guided students toward predetermined interpretations—ones that matched what I considered to be the widely accepted meanings of texts. Rather than encouraging genuine discovery, I was unwittingly steering students toward “correct” answers by over scaffolding. My how was effective in the sense that it guided them to those “correct” answers, but it was antithetical to my actual goal of helping students form the insightful and personally meaningful interpretations I knew they were capable of. If that sounds confusing or contradictory, let me explain.

Defining Interpretation

Before focusing on a more functional definition that suits my context as an English educator, consider these three definitions from literary theorists whose work I admire and who pushed me to broaden my own understanding of interpretation. There’s some overlap and points of departure between their perspectives, but each one is an invitation to consider how interpretation requires thinking beyond the four corners of the text and authorial intent (sorry Common Core).

In its broadest sense, interpretation can be thought of as the process through which we make meaning from the world around us—whether that's objects, experiences, or texts. For the purposes of this post, I want to focus on what this means for English educators. Drawing from Reynolds et al.’s (2020) articulation, I believe interpretation needs to transcend mere comprehension of the narrative or the parroting of consensus beliefs about a text’s symbols, themes, etc.

Interpretation might be best viewed as a step beyond comprehension, one in which the reader engages in the creation of a new idea from those assembled through the reading” (Reynolds, 204)

For me, interpretation asks our students to become active knowledge producers, developing their own formulations and explanations of texts based on a mix of disciplinary, background, and personal knowledge. It is a challenging thing to teach, but part of that is because its often thought of as a muscle that can only be strengthened through the brute force of repetition or as a magical gift that some kids have and some kids don’t (rather like being a wizard or a muggle). With some reframing, however, students can make marked improvement.

At this point you might be thinking to yourself “Okay. Cool theory bro, but what does all that look like in the classroom?”

Cultivating Interpretive Practices

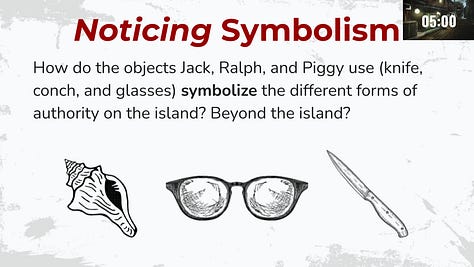

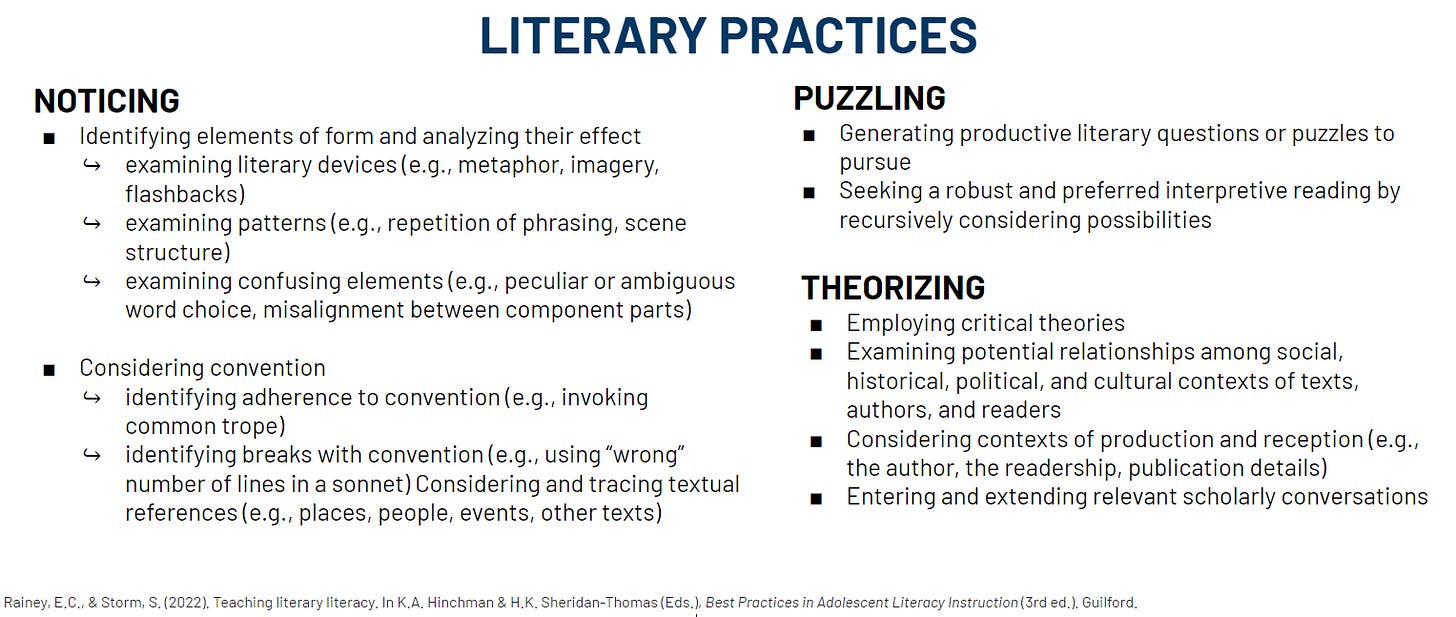

After reading the excerpt from Doing English together, I introduce my students to the key interpretive moves we’ll be using all year. Based on scholarship from Emily Rainey and Scott Storm (2022), the essential habits of mind literary scholars use when analyzing texts can be distilled into three practices: noticing, puzzling, and theorizing. These practices are foundational parts of every class I teach.

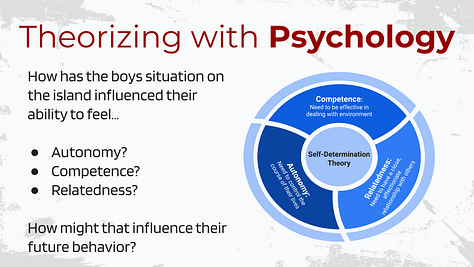

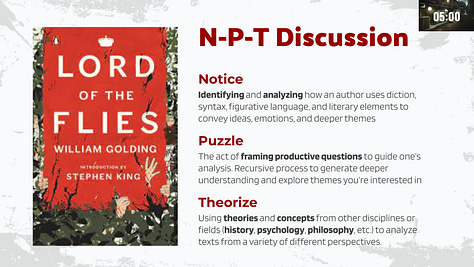

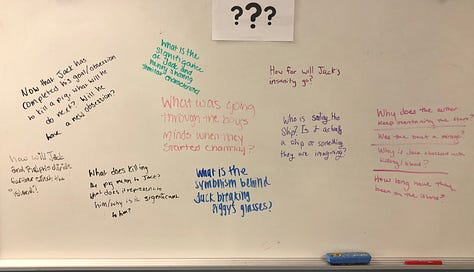

They come to life through traditional strategies all English teachers are familiar with—annotations, notetaking, classroom discourse, and various forms of self and formative assessment. The difference maker is that students now have a concrete referent that binds together a bunch of other micro-moves and skills. This shared language has been a powerful way to help students understand and articulate what it is we do when we “analyze texts” (a phrase that is clear to us, but often opaque to students). Check out how I frame them in these slides from a recent unit with Lord of the Flies.

There’s nothing earth shattering here in terms of what I’m asking students to do, but now students have a schema that provides continuity and coherence to basically everything we do in English class. Over the course of the year, the cumulative effect of that cohesion can really pay dividends.

Instead of jumping from symbol hunting in one novel to figurative language finding in a poem, to evaluating stage direction in a play, students now regard all three tasks as different manifestations of noticing form. Instead of waiting for me to tell them what to think or inquire when watching a film or reading a short story, students know they should be forming and pursuing their own literary puzzles. Instead of waiting for me to tell them they’re allowed to apply a critical lens or research the historical context of a work we’re studying, they know they’re empowered to theorize about texts in ways that help them better pursue their own lines of inquiry and form unique interpretations.

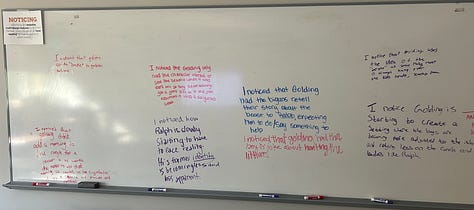

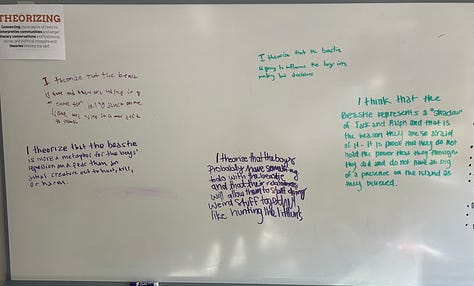

When framed this way, curriculum goes from a patchwork quilt of different texts stitched together with dozens of tiny micro-skills, to a loom that threads the key interpretive practices of the discipline throughout the entire course. One of the ways I establish and reinforce these practices throughout the year is by remixing Marisa Thompson’s “TQE Discussion” method into “NPT chats.” These crowd sourced examples of students’ noticing, puzzles, and theorizing serve as a springboard for class seminar discussions.

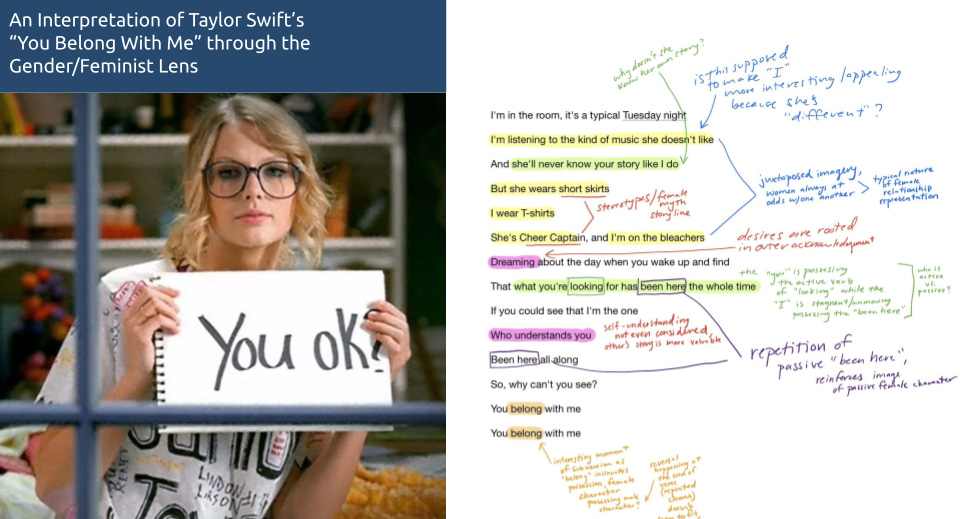

Something that is important to note about these practices is they can be applied to a variety of texts, not just novels. The only thing that really shifts are the elements of form students are noticing when they engage with texts that leverage other modes of meaning. For instance, when engaging with films, students are noticing camera angles, costumes, and set design. When they are engaging with art or graphic novels they’re noticing lines, shape, color, texture, and layout. When evaluating a speech, they’re considering gesture, vocalics, and staging.

I’ll cover this more in a future post, but if you’re not used to explicitly teaching multimodal texts, check out this resource I developed introducing key elements for visual, aural, gestural, and spatial texts.

Modeling and Cognitive Apprenticeship

Another way I support my students’ ability to interpret texts is to engage in forms of cognitive apprenticeship. For instance, I do live annotations of texts for learners when we’re in the early stages of a new unit. It’s simple enough to do. I just annotate a few lines on the whiteboard and talk aloud about the choices I make. Of course, that doesn’t mean I tell them what to think. I wouldn’t even say it means I teach them how to think in a general sense. Instead, I’m explicit about how literary experts think and inviting them to take up, remix, and try out those intellectual moves themselves. Consider this great example from one of my colleagues.

I acknowledge this approach might seem to be in tension with my previous point about the dangers about over scaffolding. I believe, however, the important distinction is that the practices I’m modeling and want them to try out come from me, not a worksheet, elaborate graphic organizer, or massive slide deck. Modeling how I engage with texts isn’t about transmitting a list of terms and skills into my students’ brains—it’s about demonstrating a particular way of tending to, thinking about, and engaging with texts. This framing emphasizes the fact I’m inviting students to participate in an interpretive community and “Do English” alongside me instead of centering schoolish, compliance-based discourses of “Doing School” (complete this worksheet, do these fill-in-the-blank notes, etc.).

Wrap Up

I’ll share more practices I use next week, but I hope you found these two useful. An affordance of rolling them out together is that they are mutually reinforcing. Developing a vocabulary around noticing, puzzling, and theorizing allows students to better recognize, name, and internalize the interpretive moves I make while doing a think aloud.

A throughline for both suits of strategies is an emphasis on fostering students ability to form their own interpretations. By being incredibly explicit about the types of interpretive practices literary scholars use and modeling them for our students, we are helping them cultivate habits of reading and interpretation that they can use to answer their own questions about texts we read, watch, and listen to in class. Importantly, these practices are portable enough to be applied to texts our students engage with every day. Lean into that! Provide opportunities for them to take up these tools to form and share interpretations of their favorite films, albums, and pieces of pop culture.

Not only are such activities ways to practice culturally responsive pedagogy, but there’s some fascinating research on the power of framing students’ learning in expansive ways that transcend the four walls of the classroom. Until next week!

References

Rainey, E.C., & Storm, S. (2022). Teaching literary literacy. In K.A. Hinchman & H.K. Sheridan-Thomas (Eds.), Best Practices in Adolescent Literacy Instruction (3rd ed.). Guilford.

Reynolds, T., Rush, L. S., Lampi, J. P., & Holschuh, J. P. (2020). English Disciplinary Literacy: Enhancing Students’ Literary Interpretive Moves. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 64(2), 201–209. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaal.1066

Love all of this—especially over break when I have a bit more space to breathe and imagine in my reflecting.

What would you say are the 4-5 essential "theory methods" that you present to your students as far as how they can enter into and work with a given text?

I love all of this! I wish cultivating literary interpretation and cognitive apprenticeship would trickle down into elementary schools. I hate being forced to teach using basal readers, making students read non-literary texts and answer comprehension questions. 😣