This is a continuation of my series examining what I regard as the three key practices of English teaching: interpretation, representation, and communication. Each post in the series is meant to stand on its own, but if you want to get the big picture check out my “Overcoming the Theory/Practice Divide In English” post. Last week, Part 1 of my “On Interpretation” post focused on cultivating students’ interpretive practices. In Part 2 I’ll shift gears and discuss the role of knowledge building in supporting students to better read the word and the world.

The Forever War

One of the most enduring, internecine debates in Education Discourse™️ is the battle between knowledge and skills. It is a polarizing issue rife with straw-man arguments, false binaries, and oversimplification. Personally, I find it one of the least productive arguments in the field. It does, however, provide a useful frame for me to articulate how I conceptualize and teach interpretation. If you aren’t familiar with the players and their plights, allow me to paint a picture of the arena:

In the red corner, we have Team Skills. They claim that knowledge is outmoded. We live in the 21st century, after all! We can just Google facts, can’t we? We don’t really need to know stuff anymore, do we? In our rapidly changing world, students need flexible skills they can apply across a bunch of different settings. What we need to do is build domain-general skills like creativity, critical thinking, and analysis!

In the blue corner, we have the new and improved Team Knowledge—bolstered by a renewed interest in (and reductive understanding of) cognitive science. They claim that we can’t think critically or creatively without having adequate knowledge of the domain we’re learning. We can’t expect kids to think critically about the Revolutionary War if they don’t know anything about it, can we? We don’t really need to waste time on application until students know a lot of stuff, do we? What we need to do is transmit knowledge to learners as quickly and efficiently as possible!

Knowledge-in-Action & Skills-in-Context

While there are pros/cons and accuracies/inaccuracies to both these perspectives, they both miss out on a vital aspect of learning—context! I actually intend to do a very deep dive on this in a future post, but for now, I’ll boil it down to two key points.

First, Team Knowledge is correct to note that (for the most part) domain general skills aren’t really a thing. The skills I use to analyze Elizabethan poetry don’t help me better analyze phase changes in Chemistry. They are distinct skill sets. Similarly, having knowledge in a particular domain does allow us to think about it with more depth and creativity. Though it’s not framed this way often, Team Knowledge is essentially critiquing the fact Team Skills fails to account for the situated nature of knowledge and skills.

Secondly, that point does little to support the pedagogies often promoted by Team Knowledge. One’s ability to recall factual and topical knowledge is only one facet of developing expertise. Even if one uses research-based methods like retrieval practice and interleaving to learn and memorize information, without opportunities to apply that knowledge, students’ understanding will remain decontextualized and circumscribed—trapped within the contrived, schoolish discourse of the traditional classroom. As Arthur Applebee puts it:

If we do not structure the curricular domain so that students can actively enter the discourse, the knowledge they gain will remain decontextualized and unproductive. They may succeed on a limited spectrum of school tasks that require knowledge-out-of-context, but they will not gain the knowledge-in-action that will allow them to become active participants in the discourse of the field

This preamble brings me to the broader point of this post—one of the foundational ways I help hone students’ interpretive practices is by equipping them with knowledge-in-action. Similar to the key interpretive practices I introduced last week (think of them as skills-in-context), teaching knowledge-in-action foregrounds the situated and social nature of learning while building the schema students need to form more sophisticated interpretations of texts.

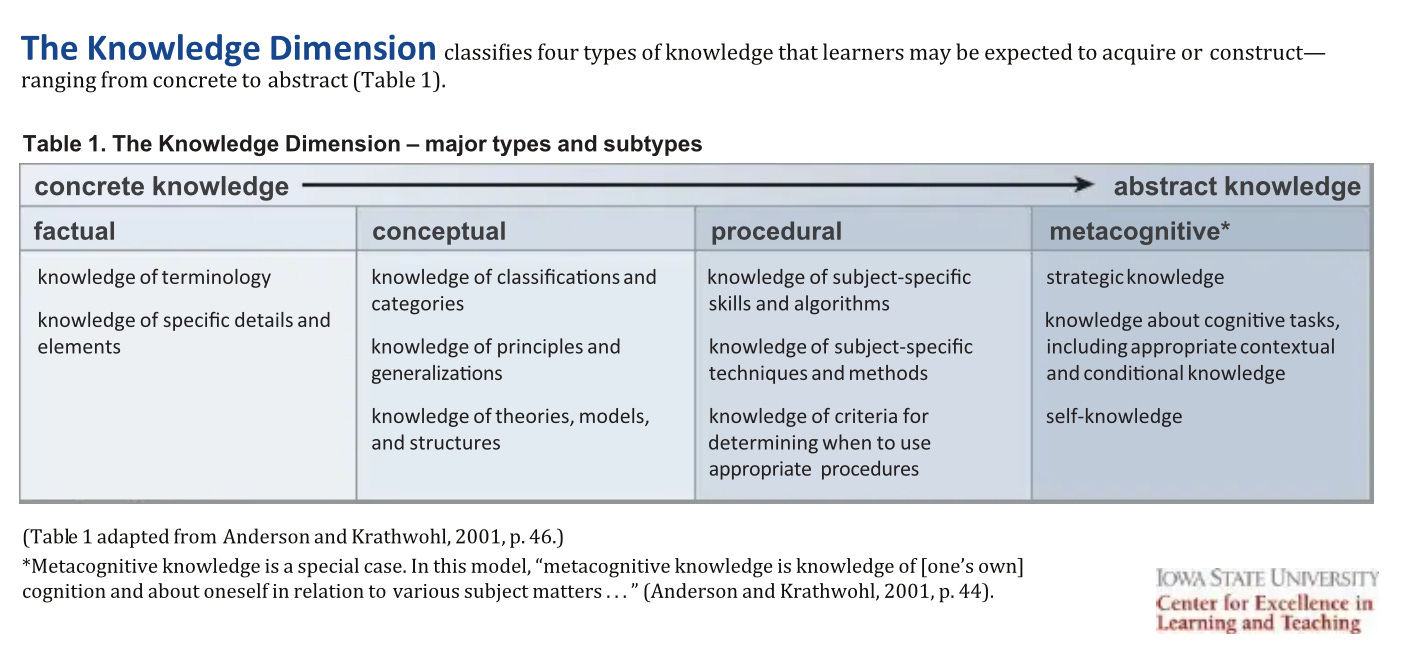

One of the key shifts in my teaching of interpretation is built off my understanding of Anderson’s and Krathwohl’s (2001) knowledge dimensions. Personally, I find this one of the most clarifying frameworks to think about knowledge. I also like that it presents the knowledge vs. skills debate for what it truly is: a semantic quibble. More importantly, it provides a sense of clarity about what types of knowledge we’re working on within a given activity, which in turn allows me to be more explicit about how that knowledge will help them better interpret texts.

Each of the knowledge types is important, but I want to zoom in on developing conceptual knowledge, as I think it’s an often overlooked dimension that, in my experience, has a large payoff. There are two ways I primarily do this: organizing learning around particular concepts and providing students with interpretive frameworks. While we can/should develop students’ conceptual knowledge about different elements of form, I want to emphasize how I use it to build humanistic and critical knowledge, as I believe my approaches to that are more interesting and unique.

Using Conceptual Knowledge to Interpret Texts

Think about conceptual knowledge as providing students with thematic lenses they can use to better notice and analyze particular dynamics in texts. For instance, one of my go-to thematic concepts is power. To introduce it, I put up a bunch of images showcasing different forms of power and ask students to write down as many different manifestations of it as they can. Then I show Eric Liu’s “How to Understand Power” TedEd video and have them sketch a visual note. I’ve shown it in basically every class I’ve taught the last few years because it provides students with an equally accessible and rich way to think about power dynamics together.

Considering how many texts revolve around shifting power dynamics, providing students with a number of examples and theories related to power better positions them to form more sophisticated interpretations. This develops into a virtuous cycle:

Students develop and refine a general schema of what power dynamics are and how they function from examples they encounter

Students are able to use that schema to better identify and interpret examples of power dynamics they encounter in individual texts

Students assimilate individual instances of power dynamics into their existing schema, deepening their overall understanding of power dynamics.

Return to 1. Rinse and repeat.

There is no better representation of the impact this can have on students' ability to read the word and the world than this meme one of my students created.

Of course, power is just one of hundreds of critical and/or humanistic concepts that you could use with this approach. It just happens to be a great jumping-off point for other concepts, themes, and theories I explore in my courses, so it’s one of my go-to’s.

In addition to using individual concepts as “lenses” through which students can view texts, I also find it powerful to provide them with frameworks and models they can use in similar ways. Currently, I’m absolutely obsessed with the “Human and Natural Systems Map” from Mark Bracher’s phenomenal book, Literature, Social Wisdom, and Global Justice: Developing Systems Thinking through Literary Study.

This is printed as a poster and hung up in my classroom. I reference it on an almost daily basis with my students—to the point where it’s become a bit of a meme. In my defense, isn’t this an incredible tool for cultivating systems thinking? Bracher (2022) refers to students’ knowledge of and ability to apply this mental model as social cognition. A term he defines as:

…understanding people as both causes and effects of multiple systems—social, cultural, economic, and natural. It also involves understanding people as themselves composed of complex psychological and biological systems involving multiple and sometimes divergent needs, motives, capabilities, and vulnerabilities (p. 13).

While empathy and perspective-taking are incredibly important aspects of liberatory teaching, I also firmly believe we must understand the systemic and structural forces that cause discrimination. According to Bracher, improved social cognition goes beyond honing students' ability to interpret texts (though it’s great for that, too) but is also predictive of shifts in their attitudes towards and conceptualization of social ills like racism, classicism, and sexism. For instance, instead of understanding a character’s (or person’s!) choice to steal food as an individual moral failure, this framework invites them to consider the impact social, economic, and natural forces had on their choice. Consider this example from The Hunger Games.

When introducing this framework to my students, I have them get in groups, select a character from a TV show, book, movie, etc., that they’re familiar with, and use it to form an interpretation. From there, it gets woven into the tapestry of our classroom discourse, and over time, it becomes a touchstone students refer to frequently in class discussions and written assignments.

Learning Literary & Critical Theory

Another way I help students develop knowledge-in-action is by introducing them to literary and critical theory. I plan to break down this topic in a future post, but I’ll focus on the knowledge-in-action aspects here.

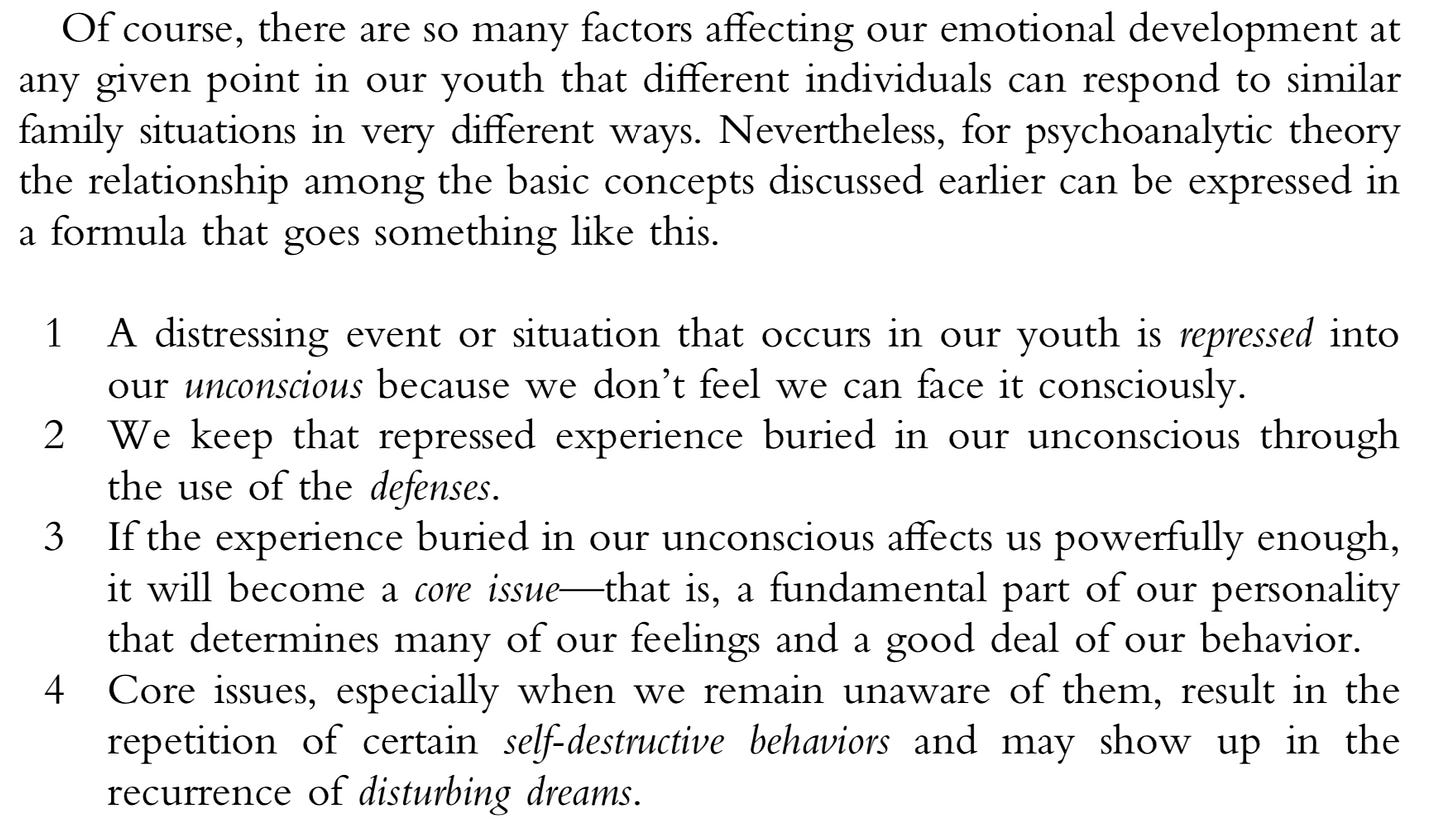

Each theoretical school operates as a constellation of concepts, principles, generalizations, and practices that students can use to build out a deeper, richer repertoire of interpretive tools. For instance, check out this framework of psychoanalytic concepts from Lois Tyson’s (2020) Using Critical Theory: How to Read and Write About Literature.

Considering English teachers frequently ask students to consider character motivations and psychological states (even if they don’t articulate it as such), how much richer and more sophisticated might their interpretation be if they had access to a conceptual toolkit like this? I introduce students to these concepts and psychoanalysis more broadly by having them do a social annotation of Tyson’s introduction and create a sketchnote they can refer to throughout the year.

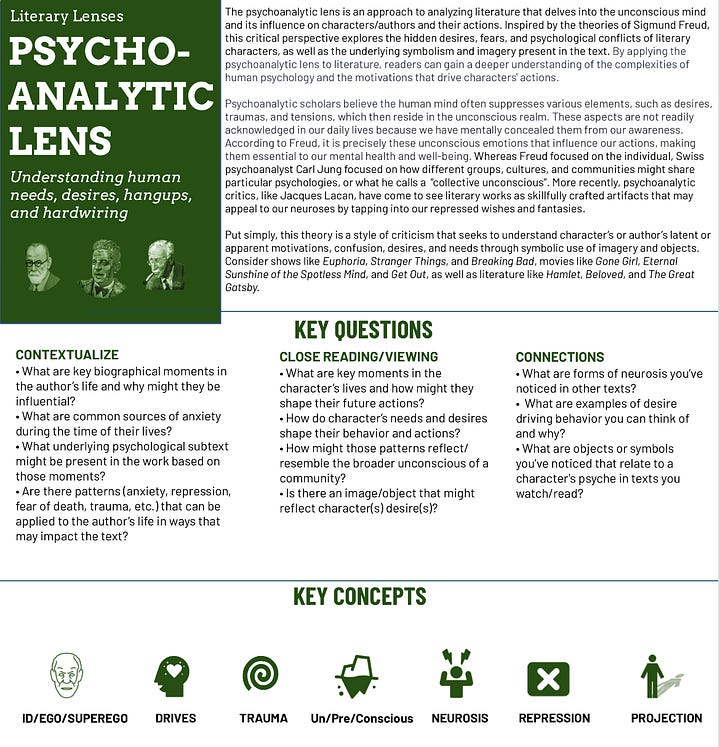

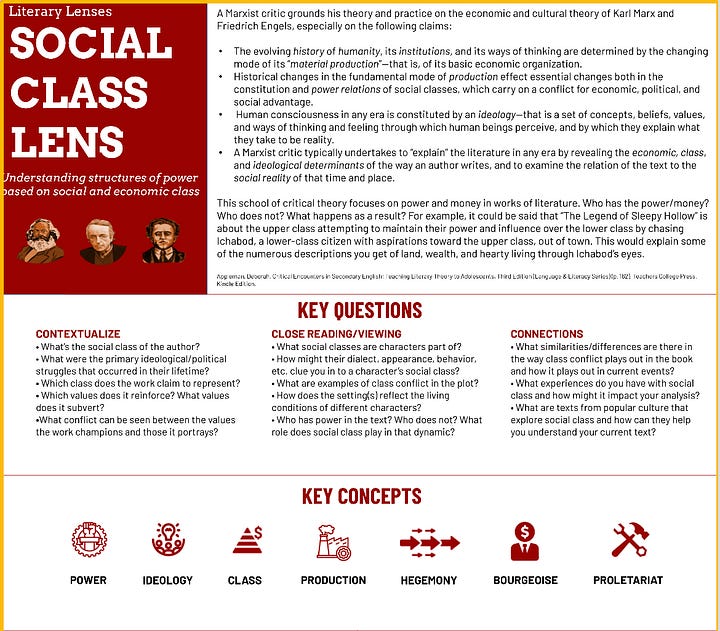

Depending on the grade level and nature of the course, I’ll also use my literary theory-one pagers to introduce students to one, some, or all four of the “literary lenses” (and their related concepts) I find my students are most drawn to. Each one-pager provides an overview of the theory, a collection of practices used by scholars in that sub-field, and a list of concepts hyperlinked to more in-depth explanations. Of course, this is but a handful of the theories available for them to use, so I plan on building more soon. Click here to access my site and download the PDFs.

Wrap Up

In essence, cultivating students’ knowledge-in-action is not about transmitting bundles of background knowledge or working out their “analytical thinking muscles”. It is about providing learners with the type of conceptual and procedural knowledge needed to become active participants in the field of literary studies. Following that, it’s equally important that students are given the time, space, and agency to use, remix, and/or subvert those tools to form interpretations that are personally meaningful and intellectually stimulating.

I hope you’ve found this week’s post useful! I’d love to hear your thoughts on these approaches and resources. How might they look in your classroom or context? Next week, I’ll discuss how students can use visuospatial thinking to better represent and understand complex text, knowledge, and social structures.

References

Bracher, M. (2022). Literature, Social Wisdom, and Global Justice (1st ed.). Taylor and Francis.

Tyson, L. (2020). Using Critical Theory: How to Read and Write About Literature (3rd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429469022

Reading all of this is so interesting for me on a personal level, as I think right out of the starting gate as a teacher I did a lot of this after having just majored in English Literature. For example, when reading Lord of the Flies, we spent considerable amount of time with Hobbes and Freud in my very first year—and then launched into the text with those lenses.

Now I'm wondering to myself: where did that go? I still dip my toe in this approach, but I'm reading this series and reimagining the entire curriculum, in a way, and it makes me very excited (and grateful) going forward. Sincere appreciation for what you're doing with this series! 🙏

Receiving that meme is a triumph.

Thank you for sharing your approach. I look forward to every post.